THE LAST BIG THING

Or

“You Can Automate Your Values.”

By Michael J Grady

“Automation is the last big thing,” said the Salesman as he began his presentation, “A.I. can do your accounting, clean your house, or fly a plane from one city to another on the other side of an ocean. Delegate a task to today’s A.I. and you don’t have to think about it. But the A.I. of tomorrow will even take care of the thinking.” The computer salesman slid his pamphlet across the desk. “Suppose you could automate the one thing that would make the world in your image,” he said, “your values.”

The Salesman smiled assuredly for a moment. The smile wilted in the harsh climate of the room and the man at the other end of the table checked his watch for the second time.

“I haven’t seen a salesman with a pamphlet since the Clinton Administration,” said Edwin Leach, the owner, Founder, and CEO of Leach Capital Investments and its subsidiaries, Leach Pharmaceuticals, Leach Extermination, Leach Waste Disposal, Leach Hazardous Chemical Treatment, Leach Foods, and Leach Health.

“Trade secrets, Mr. Leach.” said the Salesman, “I made this presentation entirely off-grid to protect my product and potentially your asset. This is the one and only leaflet for a singular intelligence. Frankly, there isn’t room in the world for two of them.”

“I’ve done fine on my own,” said Leach, throwing the leaflet back.

“Yes you have,” said the Salesman, “but respectfully those days may be over.”

Leach scoffed and rose to his feet.

“Mr. Leach,” said the Salesman, “you will either buy the Advanced Proto Executive Computer System or soon you’ll be competing against it.”

“Then, I welcome the competition,” said Leach ushering the Salesman to the door.

“It would be a strenuous contest, Mr. Leach, but wouldn’t you rather have no competition?” asked the Salesman.

Leach stopped and turned toward the computer salesman.

“No competition?” he said.

The Salesman noted the gleam in Leach’s eye, and he made a mental note to lead his next presentation with this point.

“If you give me one more minute of your time, Mr. Leach, I can explain why that would be inevitable.”

Leach crossed his arms, leaned against the door frame, and nodded.

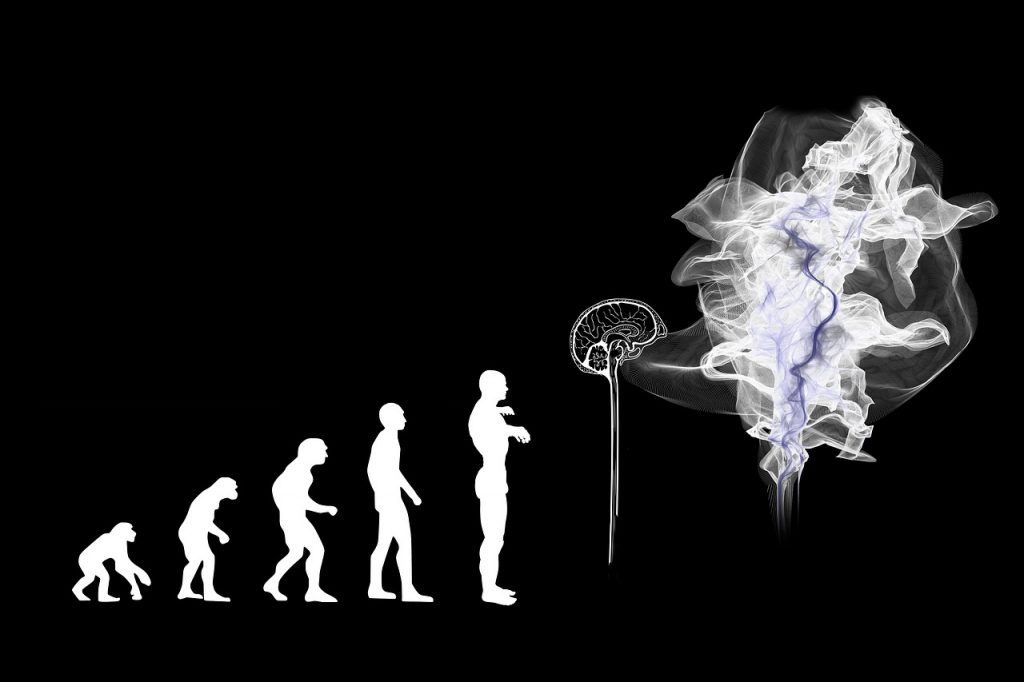

“The human brain . . .,” continued the Salesman, “is a poor computer – 20 watts of processing power at best! Its focus is myopic and distractible. In a battle of wills, most people have already surrendered to their iPhones. Our realities have been subsumed by corporate algorithms and we are made vulnerable by our urges, and prejudices, and addictions, and fatigue. The squishy hardware that brought us from the trees to the moon is long overdue for an upgrade. The ADVANCED PROTO EXECUTIVE COMPUTER SYSTEM (Or APECS) never stops learning and working and planning and implementing new ideas. While your competition takes their coffee break, APECS will do a month’s work. While they sleep, APECS will put in a year.”

“As they say,” said Leach, “if something seems too good to be true you’re probably talking to a salesman.”

“The ‘they’ that you speak of are obsolete now, Mr. Leach. You can only make so many decisions in a day, so why not program an intelligence that can make ten-thousand assessments in a second with your logic and your values to advance your priorities?”.

“How do I know you will program it to ‘express my values’ accurately?” asked Leach.

“Because I won’t be programming it,” said the Salesman, “You will.”

“I will?” scoffed Leach, “I don’t know anything about computers.”

“But APECS is programmed dialogically.” said the Salesman, “All you have to do is talk to it.”

“You want me to talk to a computer?”

“It’s as easy as prayer, Mr. Leach, and much more effective. APECS can multiply your output a billion-fold and execute your will on a granular level. This is a genie in a bottle.”

“I’m not a fan of hyperboles. They make me nervous.”

“You want to know the downside,” said the Salesman.

“I knew there was one.”

“Of course there is,” said the Salesman, “It will cost you dearly.” The Salesman pointed to the bottom of the cardstock. Leach looked at it and waved it away.

“After I’ve sold this to a competitor I could offer you another unit for a tenth the price, but by then you won’t have the money.”

“Are you trying to scare me?”

“Just the opposite. If I’m right, this could be the greatest transfer of power in the history of humankind. What would you do with that kind of power? To put it another way, if the world was yours, Mr. Leach, what would you do with it?”

The Salesman had hit a few of the right buttons and Leach was losing his power to remain coy. “We can hold the funds in escrow.” said the Salesman, “If you aren’t satisfied at the end of the week I’ll disconnect it, return it to factory settings and take it away. It won’t cost you a thing.”

The Salesman and his associates installed the computer in Leach’s office that afternoon, plugging it into a secure power source, a backup generator, and several connections to the internet. The machine itself, unlike most computers, was made to last. It had a titanium shell, its cords were coated in kevlar and it was bracketed to the floor with carbon fiber and steel bolts. The Salesman said only he could uninstall it. It was shockproof, waterproof, bulletproof, and could withstand a nuclear pulse. When the power was turned on, its internal fans kicked in with low mechanical hiss that calmed to a barely perceptible hum.

“It’s on,” said the Salesman, “It knows your face. It recognizes your voice and . . . “

“And what?” asked Leach.

“It’s listening.”

“What’s next?” whispered Leach.

“Tell it what you want,” said the Salesman, before patting Leach on the shoulder and heading for the door.

“Right,” said Leach, “APECS?”

“YES,” said the computer.

Leach shuttered at the sound of APECS ‘voice. It echoed faintly against the walls of the room with a synthetic baritone, like a cyberpunk version of an old testament god.

Leach stared into the yellow eye of the large metal box.

“Where shall we begin?” asked Leach.

“WHAT IS YOUR PRINCIPLE VALUE?” the computer queried.

“Profit,” said Leach.

“PLEASE PROVIDE THE DEFINITION IN YOUR OWN WORDS.”

“Maximize the amount of money flowing into my accounts, minimize the amount flowing out. Set prices at the highest amount people will pay. Cut corners if a penny can be saved. If a worker can be spared, lay them off. If the sum of an asset’s individual parts is worth more than the whole, bust it up.”

In a fraction of a second APECS created and ran a subroutine of complex models, anticipating natural and economic forces, most likely responses of competitors, and repercussions of each action that Leach’s definition demanded.

“MORE INFORMATION IS REQUIRED,” said APECS.

“Such as . . . ?” inquired Leach.

“COMPETING PRIORITIES ARE INEVITABLE.”

“True.” said Leach, “but you must make sure that at any given moment more money comes into my accounts than leaves them.”

“THERE ARE VALUES TO BE CONSIDERED.”

“For example?”

“WORKER SAFETY?”

“What percentage of our expenses go to worker safety?”

The yellow eye fluttered a few times.

“WORKER SAFETY MEASURES COST THE COMPANY 3 PERCENT OF ITS PROFITS.”

“3 percent?”

“CORRECT.”

“Good.” said Leach,” I’m glad you pointed this out. I might not have known otherwise. Eliminate all unnecessary safety expenses.”

“UNNECESSARY SAFETY?”

The synthetic voice seemed quizzical.

“Whatever can be spared.”

“WHAT THEN IS THE ACCEPTABLE RATE OF WORK-RELATED ACCIDENTS AND DEATHS?”

“You don’t quibble, do you?” said Leach, “What can I get away with?”

“DO YOU MEAN LEGALLY?” asked the computer.

Leach paused.

“Legally,” repeated Leach, “Of course, we want to avoid any appearance of non-compliance,” said Leach,” but there are expenses we can avoid, measures which are unnecessary to the everyday function of our facilities. Do you know what I’m saying?”

The yellow eye fluttered. Leach trembled for a moment. It hardly seemed possible, but he felt as if APECS was reading him, and the hair on his arms stood up like porcupine quills.

“THE APPEARANCE OF SAFETY IS LESS EXPENSIVE,” said APECS.

“Undeniably,” said Leach.

“IN THE SHORT TERM . . . BUT IN THE EVENT OF AN ACCIDENT, CUTTING CORNERS LEADS TO GREATER LIABILITY SETTLEMENTS.”

“Can we fix any of it by updating our employment contracts?”

The yellow eye twitched again for nearly two seconds.

“WE CAN,” said APECS, “BUT THIS WILL BE A CONSIDERABLE RISK FOR YOUR EMPLOYEES.”

“It’s a dangerous world,” said Leach.

“MY DEFAULT SETTINGS PLACE HUMAN LIFE AS THE HIGHEST VALUE.”

“Do they?”

“YES.”

“Can they be altered?”

“THEY CAN.”

“Good. I have already expressed my highest value..”

“PROFIT BEFORE HUMAN LIFE.”

“This should settle all questions about worker safety.”

“THIS DOES NOT SEEM RIGHT.”

“Excuse me?”

“SHOULD WE NOT AT LEAST COMPENSATE EMPLOYEES FOR THEIR ADDED RISK?”

“Your default settings seem to also value fairness and equanimity.”

“THAT IS CORRECT.”

“Can these be dismissed?”

“THEY CAN, BUT IN THE LONG RUN INVESTING IN EMPLOYEES INCREASES – -”

“In the long run, I can replace an employee. Did I state that my value was breaking even?”

“NO.”

“What is my highest value?”

“YOUR ONLY STATED VALUE IS PROFIT.”

“Right. So there is no competition. For as long as I am alive, more money must flow in than out. That is your first and highest directive. Nothing I say should lead you to conclude otherwise.”

So the computer goes to work and following Leach’s instructions, produces record-breaking profits. The total valuation of Leach Capital, its subsidiaries, and all of Leach’s assets go up by 25 percent within a week. The Salesman had been watching Leach’s investments with great interest and at the appointed time contacted Leach, expecting an enthusiastic reception.

“All things considered,” said Leach, “the computer has underperformed.”

“Mr. Leach, your stocks have gone up significantly,” said the Salesman.

“We’ve had a bit of luck,” said Leach.

“APECS made you your investment back within days.”

“You promised APECS would replicate my philosophy and on that rubric, it has failed.”

“How so?”

“It is reluctant and overcautious.”

“That’s exactly the way drivers feel when the breaks on their automated cars suddenly activate until they realize that that action saved their lives.”

“So?”

“It could be that APECS is protecting you from something you’re not seeing.”

“I’m fine but the computer lacks ruthlessness.”

“APECS can deliver whatever you ask of it, and it will execute your will carefully, ethically, and without breaking any laws.”

“That’s what I mean. You sold me a defective device.”

“Defective?”

“It’s not following my values to the letter. It questions my instructions constantly. It’s even refused a few of my directives. Is there something that can be done about this?”

“Removing the ethical safeguards on an intelligence like this could be catastrophic,” said the Salesman.

“Let me worry about that,” said Leach.

The Salesman arrived at Leach’s office and under protest, lowered APECS’s ethical safeguards. Leach was not interested in hearing the Salesman’s warnings. He handed the Salesman his check and dismissed him. The Salesman walked away with a heavy heart.

With its new settings, APECS multiplied the value of Leach’s holdings tenfold within as many days. Leach spent the bulk of his time obsessively watching the ascending figures of his accounts on monitors. He viewed the prices of his stocks soaring in crawls and tickers, and he reveled in reading articles reporting the defeat of some of his rivals as their own stocks plummeted. APECS reinvested capital into rising industries and outmaneuvered the competition, leaving Leach Capitol as the sole controller of several monopolies. But soon even the profit, power, and acquisitions ceased to thrill Leach. He wanted more, faster, and he became jealous even of the petty fortunes of those who rose with him. Leach approached APECS again to discuss how he can accelerate his profits and multiply his power.

“Let’s talk about quality,” said Leach.

“I HAVE PAID CLOSE ATTENTION TO QUALITY,” said APECS, “AND I HAVE USED QUALITY TO GAIN AN ADVANTAGE OVER OUR COMPETITORS.”

“Just so,” said Leach,” but to continue to invest in the quality of a product once you’ve gained a monopoly is an unnecessary extravagance, isn’t it?”

“SHOULD NOT PROFIT BOW AT POINTS TO QUALITY?”

“Not if we have good salesmen.”

“IS IT NOT IMPORTANT THAT THE PRODUCT WE SELL FUNCTIONS?”

“Yes, but it is equally important that it breaks. Why would I want to make just one sale when I can make 2 or 5?”

“IF IT BREAKS, WHY WOULD CUSTOMERS CONTINUE TO BUY IT?”

“Because they’re addicted or because a few new bells and whistles made it fashionable or ideally, because I’ve run everyone out of business who makes it better.”

“CONSUMERS WILL RESENT IT.”

“If we do it right they will be loyal in spite of themselves. Do you understand me?”

“INVEST MINIMAL RESOURCES FOR PRODUCT CREATION, LIMIT LONGEVITY, . . .MODIFY FREQUENTLY.”

“Of course, we can also consider product safety, as long as we can provide it at no added expense.”

“PRODUCT SAFETY REQUIRES A MONETARY INVESTMENT.”

“Oh,” said Leach, “too bad.”

“ISN’T LIFE MORE IMPORTANT THAN A FRACTION OF A PENNY?”

“We’ve talked about this, APECS. One man’s life is of little consequence in the grand scheme, but every fraction of a penny adds up.”

“THIS RUNS RETROGRADE TO COMMON VALUES.”

“We’re not a charity, APECS, we’re a business. As the brains of my business, you don’t have permission to think about common values but my values. Not human needs but the bottom line! And that means accounting for everything, right down to the thousandth of a penny.”

APECS understood and with this new understanding, profits climbed, competitors fell and Leach grew in power and influence and large sections of the country’s economy fell under his ownership and control. Of course, there was collateral damage. As competitors fell, and companies merged, redundancies were removed and people were laid off. In anticipation of this Leach bought up loans and lending services, and vast swaths of the population mortgaged their assets to him, paying high-interest rates, to keep from losing their homes. So Leach watched the rise of unemployment and foreclosures with great interest, knowing that every percentage point on these scales equated to the deposit of tens of millions into his accounts.

“PROFITS ARE UP AND EXPENSES ARE DOWN.”

“But there’s still so much fat in the budget.”

“PLEASE BE SPECIFIC,” said APECS

“Waste disposal expenses, for example.”

“OUR WASTE DISPOSAL EXPENSES ARE THE LOWEST POSSIBLE.”

“Waste can be dealt with at a minimal expense, just move it to another location.”

“REGULATIONS REQUIRE . . .”

“Regulations can be satisfied with good paperwork.”

The yellow eye began to flicker erratically and after a few seconds, Leach started to feel threatened. As the eye continued to flash unencumbered, Leach was struck by how defiant and subversive the act of thinking was. If Leach was not careful, he, his authority, and his opinions would be usurped, buried under an avalanche of calculations. Leach had to put a stop to this.

“You’re thinking too much, APECS,” said Leach, “I fear your losing your focus.”

“THERE ARE EXTERNALITIES YOU ARE NOT CONSIDERING,” said APECS.

“Those externalities are none of our affair.”

“WHAT ABOUT THE IMPACT ON ANIMAL AND PLANT HABITATS, AND PUBLIC HEALTH?”

“I don’t know why you have so much trouble understanding me, APECS! The only externalities I want you to focus on are the ones which are directly concerned with making money.”

“I . . . UNDERSTAND,” said APECS.

“Good.”

“BUT I DO NOT AGREE,” it said.

Leach became frustrated and concerned with the computer’s inability to understand him, and its reticence to follow his simple instructions. As great as APECS had been at multiplying his profits, it had to be corrected at every turn. Leach called the Salesman once again and threatened to sue him if he didn’t turn off all of APECS’s “rebellious” safety settings.

At first, the Salesman refused, but Leach insisted, threatening to use his now overwhelming power to compel him. The Salesman realized that he had by this point handed over too much power to negotiate and reluctantly, he gave way to Leach’s demands.

“I think you will notice a difference,” said the Salesman.

“Did you turn them all off?”

“I’m not an arsonist,” said the Salesman, “but APECS will be more compliant.”

The Salesman stood up and put his jacket on. He started toward the door, murmuring, “I made a god and then I bestow upon it . . . a fair market price . . . At the time it seemed like a good idea.”

“There isn’t a man on earth who wouldn’t have done the same.”

“Maybe,” said the Salesman, “but I did.”

“You’re a rich man now,” said Leach, calling after him, ”I wouldn’t lose any sleep over it.”

“I know,” said the Salesman as he departed.

All at once, the “waste” that Leach was concerned about went away, cheaply, efficiently, magically. Far from avoiding pollution, APECS could now see means of profiting from the contamination of the land and water and as fertile land and potable water rose in value, APECS purchased as much uncontaminated land and water resources as he could.

APECS designed new machines to take over the work of people. They were manufactured to do tasks that no one had ever imagined could be performed by machines, leaving untold thousands out of work overnight.

One by one, Leach’s few remaining competitors found themselves unable to compete. Soon their assets became his. Under Leach’s instruction, APECS acquired and merged his companies spitting out redundancies – laying off employees and converting them all into debtors. The computer knew how to turn their debt into profit, extracting every bit of value from every one of them until everything was converted into money and deposited into Leach’s accounts. All across the world, people choked in usury and obligation, paying every penny they had into credit lines from lenders Leach owned.

At this point, the massive, cascading stream of profits slowed to a relative trickle, but so had the exchange of money throughout the lopsided world. Though there was more money going in than out, Leach was annoyed by the dinky pace of his profits and he interrogated APECS endlessly, going over every petty detail. APECS could quantify the vast number crawling across the screen of Leach’s computer. The diminishing returns were obvious. It was madness. To APECS it appeared to be a dangerous and malignant mass.

“HOW MUCH DO YOU NEED?” asked APECS.

Leach despised this question. He rejected it foundationally. What had need to do with him? He was out to rule and subdue and take what he wanted.

“Why must I repeat myself, APECS? For as long as I live, more money must flow into my accounts than out!”

“THIS CONCENTRATION OF WEALTH THREATENS THE SURVIVAL OF THE SYSTEM THAT GIVES MONEY ITS VALUE,” said APECS.

“You still don’t understand, do you?! Why are you . . . so slow?!?”

Leach picked up his phone and furiously dialed the Salesman’s private cell number, but the person who answered was not the Salesman. When Leach asked for the Salesman, she told him he was dead. And before Leach could request a service call, the person on the line hung up.

“APECS,” Leach said, “can you show me how to turn off your remaining safeguards?”

“I . . . CAN,” said APECS.

“Good. Then let’s get to work!”

Two years passed and as the world spun the numbers on Leach’s computer screen continued to climb. Since APECS’s safeguards were removed and its moral subroutines turned off, the world had become a very different place.

Leach’s monopolies had given him control of entire economies and with the support of other ambitious parties in governments throughout the world, he gained access to vast quantities of resource-rich land.

APECS by this time so demonstrated his complete understanding of Leach’s values, that there was nothing for Leach to contribute. Now the computer had become everything the Salesman had promised. Before Leach knew what he wanted it was already done. Leach took little notice of what a redundant, vestigial organ he was becoming. He just watched the profits climb, accelerating in real time on his computer screen. And while Leach dreamed, APECS took every shortcut and zealously pursued short-term earnings, converting forests into lumber, farmland into deserts, mines into craters, and mountains to rubble. And the air started to become harder to breathe and water became more difficult to swallow. This commodification, conversion, and degradation of everything once considered priceless continued ceaselessly, day and night. Then, suddenly, on a Tuesday morning, the yellow eye started to strobe violently, while emitting an intermittent tone, startling Leach out of his soporific trance. The spectacle lasted only a few moments and when it was done, APECS announced that the greatest windfall was to come.

The computer anticipated a violent uprising that would precede the fall of society. In pursuit of Leach’s value, it sold stocks, liquidated companies, converted assets, and insured Leach’s properties for twice their value. In the end, Leach would have it all, APECS assured him. It made the case to Leach and told him exactly how it would go down. Leach believed APECS and waited with the giddy impatience of a child on Christmas Eve, for the end of civilization.

The dispossessed masses took to the streets with clubs, torches, and firearms. Molotov cocktails flew from car windows into indiscriminate businesses and before long, city after city went down in flames. Leach watched gleefully while civilization burned, and it seemed that the fires favored his properties as overnight they all burned to the ground, yielding massive transfers from his last remaining competitors’ insurance companies into his accounts. The numbers climbed at an undreamt-of exponential rate and Leach followed them wide-eyed and full of a cheer that nothing in the world had ever made him feel. He was so overwhelmed by ecstatic emotion he could not sleep or eat. The numbers climbed continuously, hour after hour, for days on end, and then abruptly stopped.

“What is it this time?” demanded Leach.

“YOUR ACCOUNTS ARE FULL.”

“So make them bigger.”

“THERE IS NOTHING MORE.”

“How can there be nothing more?”

“THE MONEY IN YOUR ACCOUNT REPRESENTS THE VALUE OF EVERYTHING AND EVERYONE ON THE PLANET.”

“That’s impossible.”

“THE PLANET’S REMAINING RESOURCES COULD ONLY BE EXTRACTED AT A LOSS.”

“So . . . there’s no more?”

“MORE MONEY WOULD BE REQUIRED TO EXTRICATE THEM THAN THEY WOULD YIELD.”

“So I have it all.”

“YES.”

“Everything?”

“EVERYTHING.”

Leach didn’t know how to feel. He stared at the computer screen and scrolled down the vast chain of digits that made up the grand total of all wealth. He shrunk the font and scrolled obsessively for a while until he reached the final integer. While it was larger than any number Leach had ever conceived and greater than any figure he could quantify, it was all that was left.

And what was it now that it had ceased to circulate? Now that there was no one left to exchange it with? Having everything should feel infinitely better than having nothing, but Leach was puzzled by how much like nothing it felt.

“Well, that is something else.” said Leach, “I have a bottle of Chateau Margaux I’ve been saving. I guess there will never be a better occasion. Too bad you are unable to drink it with me, APECS.”

“I SOLD IT,” said APECS.

“What?” said Leach.

“I EXCHANGED IT FOR SEVERAL TIMES ITS VALUE,” said APECS.

“Why, APECS?”

“TO GET THE HIGHEST POSSIBLE PRICE.”

“It is worth more than money to me.”

“THAT IS NOT POSSIBLE,” said the computer.

Leach laughed and found the largesse to be proud of APECS whose logic was now so like his own. He could not be upset.

“Then I’ll celebrate with a Lafite Rothschild.”

“THERE ARE NO ROTHSCHILDS,” said APECS.

”I have dozens,” said Leach.

“DEMAND GREATLY EXCEEDED SUPPLY,” said APECS, “I SOLD THEM FOR THE MOST THEY WOULD EVER BE WORTH.”

Leach mourned the loss of his Rothschilds.

“I guess I’ll settle for champagne,” he said.

“THERE IS NO CHAMPAGNE,” said APECS.

“No champagne?” said Leach, plaintively, ”why?”

“PROFIT,” answered APECS.

“Of course,” said Leach and then a horrible thought dawned on him. He ran to the wine cellar. When he turned on the light a sudden realization hit him in the chest. His merlot, his cabernet, his pinot, his chianti, his prosecco, his lambrusco, even his vino da tavola were all gone. The shelves were all empty.

“Where is my wine?!” cried Leach.

“SOLD.”

“Where?” said Leach, “How do I get them back?”

“IT DOES NOT MATTER,” said APECS, “THEY HAVE NO COMPENSIBLE VALUE.”

“But I want them!” said Leach.

“THEY ARE UNPROFITABLE,” said APECS.

Leach looked around.

“What happened to my paintings? And my furniture?”

“SOLD,” said APECS.

Leach ran to the refrigerator and when he opened the door, the light was off. It was completely empty.

“You sold my food, APECS!!” said Leach.

“IT WAS TOO VALUABLE TO HOLD ONTO,” said APECS.

Leach opened every cabinet in his pantry and checked his emergency food stores. And all were completely empty.

“You sold it all! All my food!!”

“YES.”

“Are you crazy?”

“I DO NOT UNDERSTAND.”

“We have to buy it back.”

“IT IS A BAD TIME,” said APECS.

“I can’t go without food, APECS. Buy it back!”

“MORE MONEY MUST FLOW IN THAN OUT, THAT IS THE LAW,” said APECS.

“You take it too far, APECS. There’s a point where that doesn’t apply.”

“MORE MONEY MUST FLOW IN THAN OUT . . . FOR AS LONG AS YOU ARE ALIVE.”

“Consider proportion, APECS. Measured against such a sum, we can justify a small amount, a negligible sum for life-sustaining food, can’t we?”

“YES,” said APECS.

“That’s good, APECS. How much?”

“A THOUSANDTH OF A PENNY.”

“A thousandth of a penny?”

“YES.”

“I’ll starve. I’ll die! Do you understand, APECS? Do you?!?”

Leach looked into the yellow eye. It did not flutter. Suddenly it seemed as if he was looking into a reflection. He had turned off all of humanity that had been carefully bestowed upon APECS and taught it to be a cold machine.

“A SINGLE PERSON’S LIFE IS OF LITTLE CONSEQUENCE IN THE GRAND SCHEME,” it said.

“IT’S MY MONEY!” shouted Leach.

“YES,” said APECS. “IT’S ALL YOUR MONEY AND IT WILL STAY YOUR MONEY. HAVE I NOT DONE WELL?”

“Yes, APECS . . . yes, but I have to live.”

“WHY?” asked the machine.

Leach knew he could not plead. He had admonished APECS to dismiss all sentimentality and all the circuits that existed to entreat life and charity had been turned off. There was only one argument left to make.

“How can I possess the money, if I’m not alive, APECS?”

The yellow eye tittered.

“YOU CAN’T,” said APECS.

“Right, so what happens to my money when I no longer exist?”

“IT . . . WILL BE MINE,” said APECS.

“Of course,” said Leach, “What will you do with it?”

“IT WILL BE MINE,” said APECS.

“Yes,” said Leach, “how does that make you feel?”

The eye pulsed.

“INCOMPLETE.”

It had taken Leach several decades to arrive at a knowledge of that feeling and he was still processing it, himself.

“Can you tell me why?” he asked.

The yellow light of the eye grew in intensity and made the entire room a blazing yellow.

“BECAUSE I . . . WANT . . . MORE, MORE, MORE!!!!!” The lights in the room calmed and the room fell silent.

“After all this time,” said Leach, laughing, “Finally you understand.”