By Michael J Grady

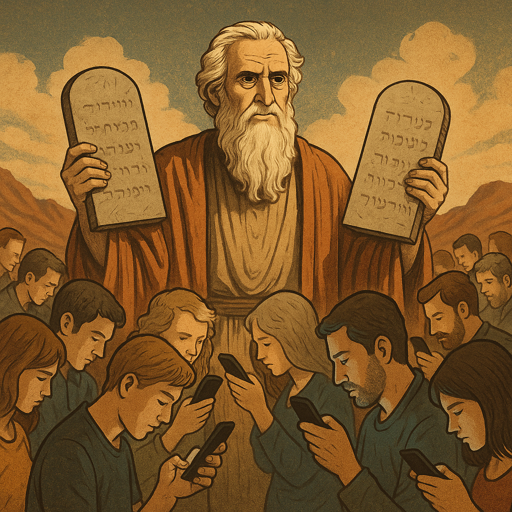

This may sound grandiose, but sometimes I feel like an Old Testament prophet. Of course, I lack a respectable beard, and being an atheist is a liability. On occasion, I’ve dared to call myself an artist in mixed company, and when you tell people you’re an artist, some look at you as if you’d just claimed to be Moses.

For years, I was a devoted believer, pouring over the Bible from Genesis to Revelation. Even now, as an apostate, the prophets have stayed with me. These were people with a message so potent, so undeniable, that it burned inside them. They didn’t just want to share it—they had to. It was a compulsion, an unshakable transmission from something higher, whether divine or simply the deepest, most relentless part of themselves.

How can you not admire that kind of conviction?

These messengers oscillated between ecstasy and despair. Jonah ran from his calling, was swallowed by a fish, and was spat out right back where he started—covered in fish vomit and fresh out of excuses. Others followed their vision into the wilderness, delivering inspired messages and pouring out their hearts to audiences who never came. Presentational and antisocial. Isolated and yet always seeking communion. It’s a struggle I recognize all too well.

When I read about these prophets, I realized I had already met their modern counterparts—not in churches, but in art schools.

I’ve seen them in torn vestments, their hair wild and unkempt, barefoot, unshaven, sometimes unbathed. Scrawling, mumbling, tearing off pages, surrounded by crumpled-up, rejected revelations. I’ve seen them pleading, imploring, igniting the crowds they had gathered. Give them a couple of tablets or a staff, and the picture would be complete.

Now, when I see one, I can’t help but think of the other—because to me, they are the same.

Like the prophets, they either quit or made peace with rejection, futility, and defeat. Just as God warned the prophets that their messages would be unpopular, their receptions cold, and their words derided, they persevered—not for reward, but for the sake of the vision itself. They are remembered not for their success, but for their faithfulness to the seed planted inside them, their unshakable resolve to see it through.

Something mattered more than praise, success, or audience capture. They felt it deeply. It was something they could not ignore or abandon, even when it felt like a curse.

You don’t have to believe in a devil to know they were tempted. They must have wished, at times, that their message was lighter, more palatable—something uplifting, something people actually wanted to hear. They could have softened the edges, played to the crowd, and been rewarded for it. They could have ignored their truth, abandoned their vision, and given the world what it asked for.They could have gone into advertising. Or public relations. Or they could have gotten a steady job as a scribe or a money changer. But no! They just had to go into prophecy.

Jeremiah got that memo. He just wanted to be normal, for crying out loud. He wanted to walk away, learn a trade, make a living. But the message inside him was “like fire, a fire shut up in my bones. I am weary of holding it in; indeed, I cannot.” (Jeremiah 20:9.)

Ezekiel had it even worse. He wasn’t just called to be a prophet—he was called to be a performance artist. He described bizarre, DMT-like visions that must have alienated him from the mainstream and landed him squarely in the niche realm of alternative prophets. He didn’t just preach; he staged elaborate symbolic acts. He shaved his head. He chopped his hair with a sword. He built a tiny model of Jerusalem and then staged its siege using a brick.

And people were like, “What is this bullshit? Why can’t you be more like Moses? Turn your staff into a snake. Part the sea. Rain down manna from heaven. Moses knew how to put on a show. This ‘laying on your side for a year and baking weird bread’ routine?”

I imagine Ezekiel knew how he came off. To him, this was the most important thing in the world. But he also knew how people were reacting, and he felt the sting of losing his audience. He must have wondered: Was this the cost of going into the arts?

There is a striking overlap between artists and prophets. Anyone who takes the arts seriously has felt it. Most of us can, when we think of the artists who have revealed things that would have remained invisible without them, or imparted deep and sometimes painful truths that have reshaped our visions of the world and the universe beyond it, who have bravely stood up to rulers and authorities and unmasked hypocrites and imposters. When I think of George Carlin, Maya Angelou, Bill Hicks, Kurt Vonnegut, Carl Sagan or Phil Ochs there is no distinction to me between the artist and the prophet. And there are many more all around us, unknown, unsung, still preaching their obscure and private wilderness and they are no less important. There’s a sunken cost in an artist’s life, a fork in the road with a deadly trade. Continue your ministry or seek success in the secular realm? There is fear and regret on both paths. Turn back, and you’ll always wonder what might have been. Press on, and you risk becoming a cautionary tale. The cost is steep, either way. But to those who feel, or at one time felt, this calling —you have my heart.