Bombast knew he had that thing that everyone wished for, but few people had: a sense of destiny.

He knew — from the tip of his nose to the corns of his feet — that he was born to greatness, and the humble place he occupied now was just the ending of the first act of the greatest success story of his generation.

This was the day!

The long-held bubble of glee was just minutes away.

How would he contain himself?

He smiled at his reflection on the surface of his cup of black coffee — a beverage he had grown accustomed to over many long, sleepless nights preparing for today.

As his agent entered the coffee shop, Reginald tried not to seem too keen, too knowing.

He had to be humble, if only for another few minutes.

And the check — that massive, life-changing check!

What would he do with so much money after so many lean years?

Llewellyn, his agent and brother-in-law, seemed cool as a cucumber.

How could he stay so calm, knowing that he was about to sit down to the most momentous meeting of his career?

He was nothing if not a professional.

With a man like this at his side, surely Reginald would go far.

Reginald straightened his back and rose to his feet as casually and personably as he could manage under the circumstances.

His knowing grin looked passably enough like a friendly greeting.

“Llewellyn, you’re early,” said Reginald.

“I was hoping to get here before you to prepare myself,” said Llewellyn.

“Ah,” said Reginald. “Good news travels fast. Isn’t that always the case?”

“I listen to the traffic report,” said Llewellyn. “And the 93 was clear.”

“That’s perfect,” said Reginald, chuckling. “It looks like things are finally going my way.”

“Really?” said Llewellyn, smiling awkwardly. “Tell me all about it.”

“Well, you know,” said Reginald, starting to feel a little antsy. “I’ve been really looking forward to seeing you. It’s been on my calendar and here we are,” he said, looking for more emphasis, “finally.”

“Yes,” said Llewellyn, looking down. “Finally.”

Something wasn’t right, thought Reginald.

He looked around to see if anyone was hiding.

Were there any hidden balloons?

Was someone about to come out with a cake loaded with lit sparkles?

The moment passed, and Reginald started to get angry.

“What did they say?” asked Reginald, desperately.

“They said ‘no,’ Reggie.”

“No,” said Reginald.

“Yes.”

“Yes?”

“No.”

“But—” said Reginald, at a loss, “what?” and then all his thoughts collapsed into, “why?”

“It’s not what they want.”

“Why?”

“It’s not what anyone wants,” said Llewellyn. “No one is looking for a children’s book with footnotes.”

“How are they going to understand it without footnotes?”

“Exactly.”

An uncomfortable silence drenched the room.

It was feeling humid, Reginald thought.

His face was getting hot.

“I worked so hard on those books, every volume.”

“They’re just too complicated,” said Llewellyn.

“You can’t pander to children. They’ll see right through it.”

“Sure, you can’t pander to them, but you also shouldn’t terrify them. And those titles.”

“As a child I would have loved The Lackluster Canard of the Laconic Sycophant, The Obstreperous Patois of the Persnickety Fabulist, or The Preposterous Malfeasance of the Peripatetic Bumblebee.“

“And I barely understand what any of those mean.”

“Well, maybe that’s your problem,” barked Reginald. “Have you thought of that?!”

Llewellyn sighed and looked down at his coffee, as if it might offer a way out.

No such luck.

The appointment ended awkwardly, with Reginald going through three stages of grief while Llewellyn quietly made his way through five.

Later, Reginald sat at his desk, glaring at his bookshelves.

The rows of self-published hardcovers stared back at him like silent disappointments.

He muttered to himself, pacing.

“Years. Years of work. No recognition. That hack Llewellyn — what does he know? Married my sister and thinks that makes him an editor.”

He looked at the calendar, where a bright pink circle marked Thursday — Community Author Talk.

He sighed, picked up the phone.

“Local Arts Council, this is Margery.”

“Hello, Margery. This is Reginald Bombast. I’m afraid I have to cancel my talk. Circumstances beyond my control, I’m afraid. It simply won’t be possible.”

A long pause. Then: “Oh, Mr. Bombast… this is so embarrassing.”

“I understand, but… you know.”

“Yes,” she said. “I just did so much work to organize it.”

“I’m sorry,” said Reginald.

“If you knew what I had to do to arrange for the funds.”

“What funds?”

“For your fee.”

“My fee?”

“Yes. $300.”

“$300?”

“Yes.”

Reginald stared into the void.

That isn’t very fair, is it?” he said.

“It’s okay. I’ll call my backup. I’m sure—”

“And burn that bridge? After all the work you did to organize this? How could I live with myself if I just left you hanging like that?”

“But your situation—”

“I’ll figure it out.”

“There are more important things than this talk.”

“Sometimes sacrifices have to be made,” said Bombast.

“I can’t ask—”

“You don’t need to.”

“Are you sure?”

“Can I get paid in cash?”

“Yes,” said Margery.

“Of course, I’m sure.”

“Thank you, Mr. Bombast. We’re all so excited that you’ve agreed to speak to us.”

After hanging up the phone, Bombast felt back in the game.

Soon, he would be a professional lecturer on the art of children’s literature.

Put that in your pipe, Llewellyn! he thought.

He caught his reflection in the mirror and paused.

With some effort, he decided, he could grow a fairly visible mustache.

He pulled a few experimental faces, imagining how it would look on a dust jacket.

How could anyone with such a literary countenance fail to succeed?

Energized, Bombast grabbed a clean legal pad.

After testing several titles, he settled on the perfect one:

“Treating Children As Adults.”

Yes.

This was the message!

He loved it so much he briefly considered tattooing it on his hand.

It captured the essence of his philosophy — the change he most wanted to see in the world.

He filled three legal pads with impassioned notes, refining them carefully at his word processor, shaving and smoothing until he had shaped the lecture he knew the world needed.

Perhaps this, too, would be published.

Perhaps it would be studied.

When he was done, he admired the final result:

a tight, four-hour lecture.

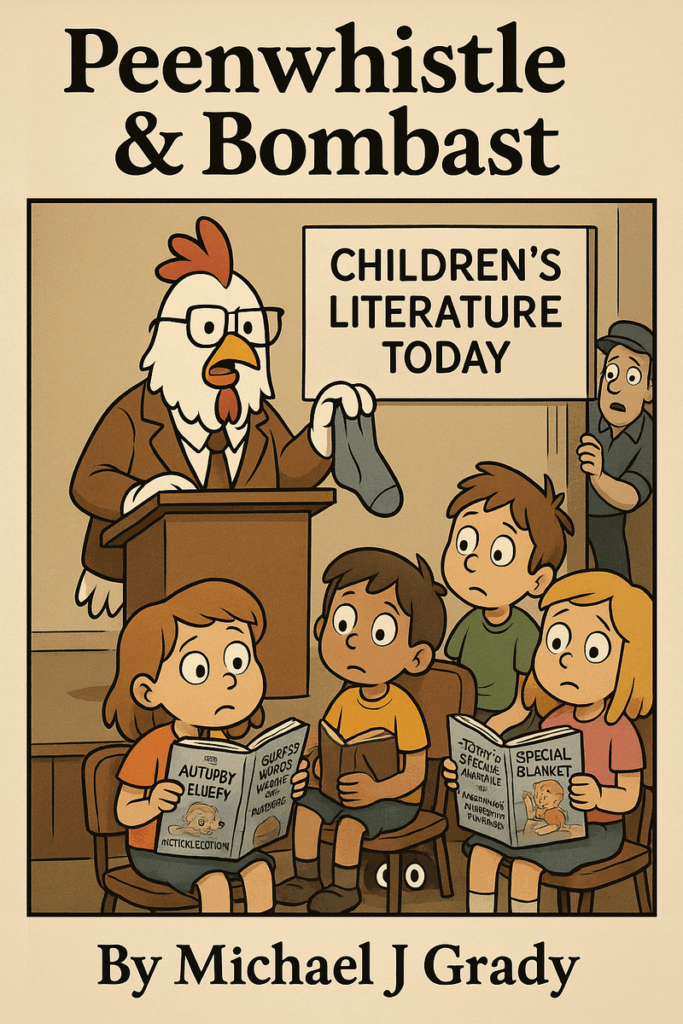

When the day came, Bombast carried all his enthusiasm into the room with him.

There was something about being prepared — about knowing he was armed with the unassailable truth.

As Margery introduced him and scattered applause rose from the audience, Bombast felt something ignite inside him.

It didn’t matter how small the crowd was.

They were his.

They just didn’t know it yet.

Bombast plunked his speech onto the podium with a snap that echoed around the room, making a few in the audience twitch.

“The time has come — at last — for children’s literature to grow up,” said Bombast.

He paused for applause, as he had rehearsed — but the room was silent.

One man in the third row shifted forward slightly, almost ready to clap, then thought better of it.

Bombast pressed on.

Twenty minutes later, that man had either moved to the front row or everyone in front of him had left.

Bombast chose to believe the former.

People began standing up — heading toward the bathroom — and not returning.

By the end of the second hour, everyone had gone to the bathroom except Margery, who clutched her program like a life raft until nature forced her, too, to flee.

When Bombast reached the conclusion of his lecture, there was only one person left:

a bright-eyed, zealous man who leapt to his feet and applauded as if salvation itself had arrived.

Bombast froze.

There was something unsettling about the man’s fervor.

He glanced at the exit, gauging the distance, but there was no easy escape.

“That was incredible!” said the man.

“Oh, uh, glad you liked it,” said Bombast, edging toward polite.

“I loved it!” said the man. “As I heard it, I thought — finally, finally someone understands!”

“Thank you.”

“And of course it was you,” said the man. “I’ve read all your books. I think you’re the only competent children’s writer working today.”

Bombast stiffened, both flattered and horrified.

He hadn’t sold many books — he knew the exact number: four.

“How did you get them?” he asked.

“My cousin Brenda,” said the man brightly.

“Brenda Stevens?”

“Yes.”

Bombast remembered.

He had dated Brenda for a few months and, just before she broke up with him, gifted her his complete collected works.

“And she gave them to you?”

“Sort of,” said the man. “She was holding a garage sale.”

“Oh.”

“They were in the discard pile.

Lucky for me — they changed my life!

That’s why I’m here.”

“They really changed your life?”

“Oh yes. When I read them, I knew: here was a genius. Finally.”

“Wow,” said Bombast, still trying to process it.

“Would you like a cup of coffee?”

“Sure,” said Bombast.

Bombast left with the strange man, uncertain whether he was heading toward the greatest praise of his life or being discovered by a golden retriever on a morning jog.

They sat for a while in the coffee shop, the awkwardness growing between them like a slow leak.

“Would it be okay if I showed you one or two of my children’s books?” asked the man.

“You mean the ones you wrote?”

“If you don’t mind. I’d love to hear your thoughts — and I’m sure you’ll spot one or two homages among them.”

“That sounds… great,” said Bombast, at once eager to leave and reluctant to abandon what might be his only fan.

On the day Reginald Bombast visited Leonard Peenwhistle at his home, he was greeted at the door by Leonard’s older sister, Mirabel, who ushered him into the living room — a space transformed into a shrine to Leonard’s work.

Illustrations hung on the walls.

Books lay open to select passages.

Others were stacked in unstable towers on chairs and tables, turning the room into a curated maze of narrative.

Reginald noticed the collection at once and felt instantly overwhelmed.

One step would place a wall between him and the front door; two steps would surround him with Leonard’s impressive oeuvre.

Leonard waved him in.

Reginald hesitated, suddenly feeling like Little Red Riding Hood stepping into Grandma’s house.

“Feel free to look around,” said Peenwhistle, “and let me know if you have any questions.”

“Sure,” said Reginald, now feeling like a maid asked to spin straw into gold.

He scanned the towers of handwritten spines.

As enormous as the collection was, Reginald found himself unable to move beyond the sheer scale of it — not just the physical mass, but the weight of intention, of effort.

The room felt less like a living space and more like a shrine no one had asked for.

“Oh, I should tell you,” said Peenwhistle, boastfully. “I got a grant — thanks to you.”

“You did?”

“Yes. I quoted you extensively in my essay, along with Bruno Bettelheim and Edward Bernays. They ate it all up, and in the end, they awarded me thirty thousand dollars.”

“What?” said Bombast, hoping he had misheard.

“Thirty thousand dollars,” repeated Peenwhistle.

“To write?”

“Imagine,” said Leonard. “For the next year, all I have to do is explore my voice as a writer.”

“That’s unbelievable,” said Bombast, feeling profoundly morose.

“If I break through,” Leonard added, “I owe you a great debt for my success.”

He turned toward a nearby stack.

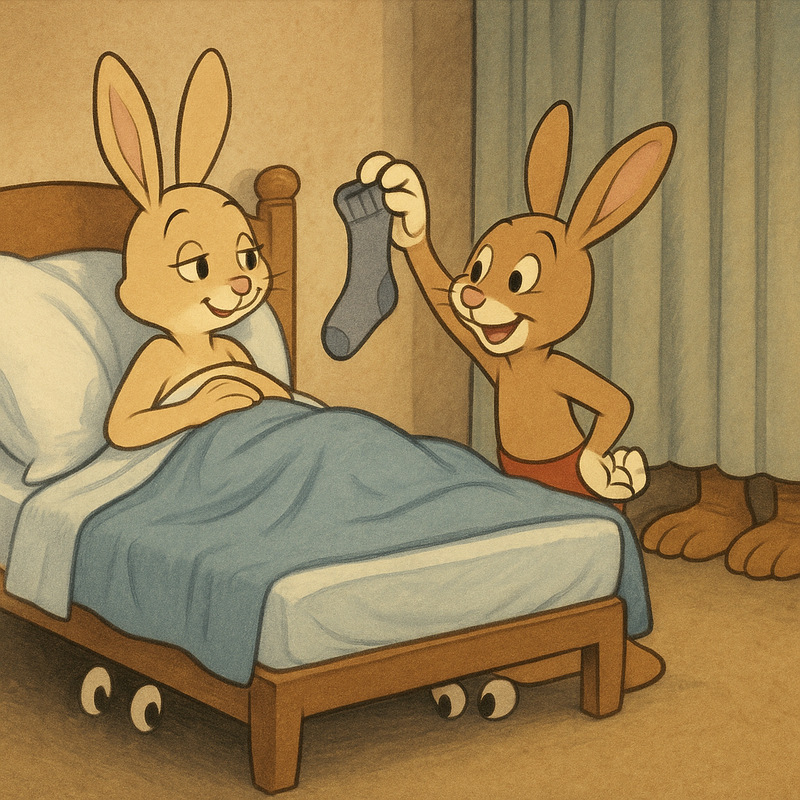

“This one is called Fuzzy Boinkington’s Big Surprise! Would you like me to read some?”

Bombast swallowed hard. “Okay.”

“Fuzzy Boinkington was vigorously buffing his snizzlepump when a sharp rapping at the door sent his twerpnoodle jolting like a startled jackalope. He checked his watch, hastily tucked his pibbles, and bounded to the door, barely suppressing the tribbling in his snizzle.

“Smoothing his fur, he swung open the door to find Mrs. Dinglepuff, wrapped in wispy fluffentuft — the sheer fabriscosence doing little to obscure the teasing sway of her labenstroodle. Boinkington’s eyes caught the impish peep of her tiddlyfluffs, wobbling jauntily above the folds of her fluffentop.”

Reginald’s left eye began to twitch involuntarily.

He was becoming confused.

Profoundly so.

“Fuzzy swallowed hard,” continued Peenwhistle, his voice impassioned, “his snizzle trembling at Ms. Dinglepuff’s soppiant twinkle. Her spoofdoogles drifted lazily over Boinkington’s quivering snizzlecap. Then, with a knowing smirk, he reached out, klooning the crevakases of her pumperdumps as her fluffentuft slipped slooshingly to the floor.”

Reginald realized he was sweating.

He was becoming very lightheaded, and he was trying — with increasing desperation — to convince himself that “pumperdumps” was another word for mittens.

“Fuzzy’s twerpnoodle shoomed with uncontainable fervor into the floomenfolds of Dinglepuff’s stroodlewumbles. The room quaked with pampusculent juddering, vociferous hoohoos, and the squishy slosh of rhythmic plooping — until Boinkington’s volcanic pumpusculence erupted, plunking onto the glistening topoference of Dinglepuff’s tumiscitude.”

Reginald realized he was forgetting to breathe.

That can’t have meant what it sounded like, thought Reginald. Maybe I’m jumping to conclusions. Maybe I’m just low in iron.

“Would you like to see some of my illustrations?”

Reginald wasn’t sure — but they might clarify a few things.

“Okay,” he said, very softly.

He was beginning to feel frightened.

Leonard handed him a small portfolio.

The drawings brought everything into stark, horrifying focus.

They clarified the meaning of “rhythmic plooping,” revealed the anatomical location of the “snizzlepump,” and defined the exact surface area of the topoference upon which Boinkington had plunked.

This did not make Reginald feel better.

In fact, it made him feel very lightheaded — and then, quite suddenly, everything went brown.

He awoke to the smell of ammonia.

Peenwhistle was standing over him, holding a small vial of smelling salts.

“Mr. Bombast?” he said. “Are you okay?”

“Yes,” said Bombast. “I think so. I must have passed out.”

“Some people find my writing overwhelming at first.”

“I can imagine.”

“Of course, you can.”

“Yes.”

“So, what do you think?” asked Peenwhistle, smiling.

“Well…”

“Don’t you like it?”

“Like it?” said Bombast, completely at a loss, “well, ah… you see.”

“You hate it.”

“No, no… no, not hate.”

“You don’t like it?”

“That’s not what I said. I, I, I… I just think it should be more…”

“More?”

“Or less, perhaps less… ah, maybe I just need to get a sense of your entire… ah, oeuvre.”

“Oh.

“Mr. Peenwhistle, maybe we should move away from the stories of fanciful creatures into something a little more… ah, concrete. Do you have any more… conventional stories?”

Bombast, flipping through another volume, squinted at the title:

“The Farmgirl’s Pu—.”

Reginald froze.

“Peenwhistle… what exactly is this?”

“Oh, that one’s part of the Farm Friendly series. Teaches responsibility.”

“And this one?” Bombast lifted another:

“The Handyman’s Caulk.”

“Yes!” said Peenwhistle, lighting up. “A favorite of mine. It’s got a fun rhyme.”

He cleared his throat and recited:

Handyman caulks

Handyman screws

Handyman nails

with a handyman’s tools.

Bombast shut the book slowly, as if afraid it might bite.

“What are these supposed to be?”

“They teach children positions.”

“…You mean occupations.”

“If they’re so inclined.”

“Well, I do have this story that I’m working on that’s a little more conversational in nature.”

“A dialogue?”

“Yes,” said Leonard, “does that sound too boring?”

“No, no, that sounds perfect. What is it called?”

“The Cock and the Swallow.”

Bombast felt as if his soul had left his body.

“Are you making fun of me?” Reginald asked.

“Of course not,” said Leonard. “You, of all people, know how important this kind of work is. I was going to ask you for a quote to put on the back cover.”

“How about the front cover?”

“Of course. What would you like to write?”

“Keep out of the reach of children.”

“Now you’re making fun of me,” said Peenwhistle, frowning.

“Not at all,” said Bombast. “I’m being serious.”

“Then you’re a hypocrite,” snapped Peenwhistle. “You’ve spent years advocating for a vision of YA that doesn’t condescend to children — and now, the moment someone else achieves it, you try to shut them down.”

“This isn’t what I was doing,” said Bombast, “or what I meant to do.”

“What did you mean to do?”

“I… just wanted to write something good. Something different. Something… that resonates.”

“So do I,” said Peenwhistle. “Exactly that. It’s my dream, and I haven’t given up on it.”

“But you should,” said Bombast. “You really should.”

“What would you say to someone who suggested you give up your dream?”

Bombast didn’t answer at first.

Then: “Now?… Now,” he said again, “I think I just did.”

He walked all the way home.

When he arrived, he went straight to bed.

He slept until noon the next day.

When he finally got up, he cleaned his apartment — starting with the bookshelves.

By sundown, his typewriter was on the curb, along with every book he’d written and all of his notebooks filled with ideas.

He wanted to cry all night, but instead he closed his windows and went back to bed.

And it rained until morning.

Without writing, Bombast didn’t know who he was or what to do with himself.

He tried everything he could think of to occupy his mind, but nothing stuck.

And then he’d have a novel thought, or a phrase would land on him with a habitual burst of excitement,

and his eyes would shoot to the bookshelf —

but it was empty.

At night, Reginald would have terrible dreams.

His mind was full of titles for books that should never be written:

POINDEXTER THE PANDA’S CATASTROPHIC ORGAN FAILURE

CURIOUS GEORGE DISCOVERS PORNOGRAPHY

WILE E. COYOTE’S SUICIDAL IDEATIONS

SNOW WHITE AND THE SEVEN HOLES

EVERYBODY POOPS, BUT NOT LIKE UNCLE GARY

TOMMY’S SPECIAL BLANKET AND THE SUFFOCATING EMBRACE OF AN INDIFFERENT UNIVERSE

THE AUTOPSY OF FLUFFY McTICKLE-BOTTOM

DON’T WAKE DADDY, HE’LL JUST START CRYING AGAIN

GUESS WHO’S UNDER THE FLOORBOARDS?

They came one after the other, night after night.

Reginald would wake from panic attacks and dread going back to sleep.

Soon, he spent all his time walking — through neighborhoods, through parks, anywhere —

until one day, he didn’t even feel like going home.

He lost track of time.

He stopped caring whether it was day or night.

He continued walking in a fog, barely noticing how long his beard had grown or how his coat was coming apart at the shoulders.

Reginald thought about ending his life, but didn’t know how.

He couldn’t think of a way to transition into non-existence that didn’t sound ghastly to him.

So, he turned to the Universe and asked for a sign — anything to tell him what to do, what to become.

Just then, while walking past a bookstore, the Universe gave him one:

LEONARD PEENWHISTLE — AUTHOR READING & BOOK SIGNING!

Bombast pleaded to the heavens:

“Any sign… but not that one!”

Reginald wanted to turn away, but he was pulled by something he could not resist —

the feeling that he was in a story and that he had to find out what happens next.

Though Reginald wasn’t fond of this story, he had to find out what happened next.

Peenwhistle’s voice echoed over an attentive and oddly animated crowd.

Reginald immediately felt like the odd man out — because he was the only man there.

The room was packed with people in plush animal costumes.

Whiskers twitched. Ears flopped.

And at the front of the room, presiding over them all, stood Peenwhistle like a preacher at a pulpit:

Mr. E’s “E”-ness is common to his genus,

It’s filed in his drawers between his “A”-ness and his “P”-ness.

If you decide to pull it,

Be careful you don’t faint —

Few will ever mention what it ’tis or what it ’taint.

The room erupted with the sound of 150 pairs of faux fur mittens clapping joyously.

As Reginald looked around, it felt as if he were trapped inside one of Peenwhistle’s books.

Peenwhistle picked up Fuzzy Boinkington’s Big Surprise and the room went positively bananas.

The animals in attendance howled, hooted, and cawed with wild and woolly recognition.

Shortly after Peenwhistle began, the plushies slowly started to caress one another.

The room began to trill and purr with growing enthusiasm.

Reginald stood in the midst of it all, deeply disquieted.

He stepped outside the room and started to scream:

“THEY’RE BUFFING THEIR SNIZZLEPUMPS! THEY’RE BUFFING THEIR SNIZZLEPUMPS!”

The manager on duty tried to calm Reginald, but he continued to shout:

“I WON’T CALM DOWN! I’M NOT THE PERVERT HERE! CAN’T YOU SEE IT?”

“Please calm down, sir, or I will have to call the police.”

“YES, CALL THE POLICE AND TELL THEM THEY’RE… THEY’RE… SHROOMING AND KLOOING THEIR… CREVAKASES AND… PLUNKING THEIR TOPOFERANCES! AND FOR ALL I KNOW, GILING AND GIMBLING IN THE WABE!”

A man placed his hand on Bombast’s shoulder.

“If you can’t quiet down, you have to go.”

“Fine,” said Bombast. “I’m leaving.”

Bombast wiped his forehead with the back of his sleeve, feeling suddenly and entirely spent.

He didn’t know where he was going.

He just started walking.

At the corner, a sidewalk display caught his eye — a row of glossy new books stacked neatly in the sunlight.

He moved closer without thinking.

“The Lackluster Canard of the Laconic Sycophant,” he said, picking up a copy.

He thumbed through the book; it was his.

For a moment, he wondered if he was having another bad dream.

“If you want that book, you’ll have to pay for it,” said the vendor.

Bombast smiled, almost sadly.

“I was going to say the same thing,” he said, before carefully putting the book back.

“It’s a top seller,” said the clerk.

Bombast lifted the book once more and turned it to the spine, which said:

by Llewellyn Puttupon.

He smiled again, almost a real smile this time.

“I always knew it would be,” said Reginald, walking out.