By Michael J Grady

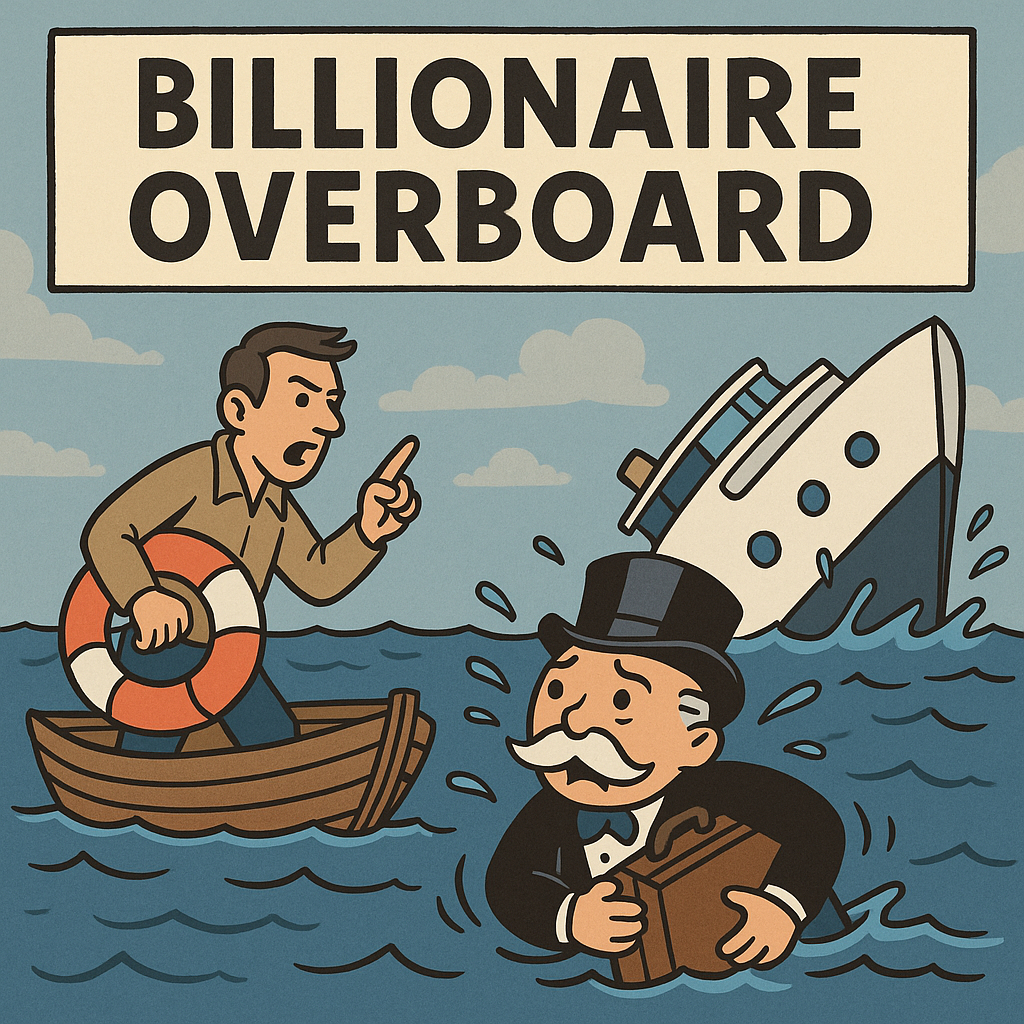

While rowing out to sea, I saw a yacht sinking slowly into the ocean. I paddled out, stopping occasionally to take pictures, and, by the time I made it out to where the yacht had been, there was only a single billionaire left, clinging to a sinking parcel of Louis Vuitton luggage.

“Help!” cried the Billionaire, “or I’ll sink!”

I looked around and rowed out to him.

“Did you say something?” I asked.

“Thank God you’re here,” said the Billionaire, “I knew someone would. I was just throwing a party with a few hundred friends. We hit a rock which punctured the hull, and the yacht went down, taking dozens of my peers – captains of industry, corporate kings, fat cats, and magnates – down into the abyss.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, rowing a little closer..

“Don’t be,” said the Billionaire, “It took care of my fiercest competitors. A few phone calls after I get ashore, and I’ll make a killing.”

“Congratulations,” I said.

“You may be looking at the last billionaire on Earth,” the Billionaire bragged. “By tonight, I may even be a trillionaire!”

“What a stroke of luck,” I thought to myself, stopping ten yards away from him.

“Why did you stop?” the Billionaire asked.

“Just thinking,” I said.

“What are you waiting for?” asked the Billionaire, “Quick, throw me a life preserver!”

“I would,” I said, “but the last thing you need is a handout.”

“What?” asked the Billionaire, appalled.

“A man has to stand on principle,” I said.

“I can barely stay afloat,” pleaded the Billionaire.

“There’s dignity in struggle,” I said.

“But I’m sinking!” said the Billionaire.

“That’s because you’re not putting in the work” I replied, as I started to row away.

The Billionaire started to splash violently at the waters.

“Can you throw me a rope?.”

“Pull yourself up by your bootstraps,” I said.

“My bootstraps are sinking,” said the Billionaire, as his parcel sank beneath him.

His whining was starting to spoil my fun and my patience was starting to wear thin.

“You have to change your mindset,” I said, “have you tried visualizing yourself floating?”

“I’m going to drown!” cried the Billionaire.

“Some of the best swimmers started out drowning.”

“And some of the worst ones end up dying.”

“That would be a great lesson to you,” I said.

I thought I had made my point, and I was starting to get hungry, so I grabbed my oars, to row back.

“You can’t leave me,” demanded the Billionaire

“Why not?” I asked, “What kind of society would this be if we just bailed everyone out who got themselves in over their heads?”

“I’m drowning,” said the Billionaire, indignantly.

“And whose fault is that?” I asked,

“But you have the means to save me,” he pleaded.

“I’ve been where you are, Mr. Billionaire, and nobody saved me,” I said, wagging my finger at him. “If I saved you, I’d be doing you harm. No, no, no, you don’t really want me to save you,” I said.

“Yes, I do,” he insisted.

“If I saved you today I’d just have to save you again tomorrow. You’re drowning because you won’t swim, and you won’t swim because you’re lazy.”

“What are you talking about?” said the Billionaire, who started flapping at the water with an indignation that I did not appreciate.

“Why should I save you, if you refuse to save yourself?” I said.

“I can’t swim,” said the Billionaire.

“Not with that attitude,” I said, “no one is stopping you from swimming ashore.”

“I don’t know how,” cried the Billionaire.

“Then clearly you couldn’t be bothered!” I said,“If I saved you, I’d have to save everyone, and then where would we be?”

“Easy for you to say,” said the Billionaire, “you’re in a boat.”

“And that is how meritocracy works,” I said, picking up my oars again.

“But you must save me,” said the Billionaire.

“Must save you?!” I said, throwing my oars back into the boat.

“Yes,” he said.

“What am I, your slave?” I said, bitterly, “You want me to save you at the point of a gun? That’s not freedom. If I begrudgingly obey your command to save you, today. Next thing you know we’re living in Russia!”

“Letting me die would be immoral.”

“Whose morals?” I asked the Billionaire, “Stalin’s?”

“Out of the goodness of your heart, then,” he said, slapping the water with desperation.

“Charity should be voluntary,” I replied, “given freely, not coerced and manipulated.”

“But there’s no one else here to ask,” said the Billionaire.

“Perhaps,” I said, “but it isn’t MY job to save you. To expect that I help you without compensation is theft, if you ask me. What you need to do is take responsibility for your actions.”

I began to row away, and the Billionaire clutched at his sinking luggage until it disappeared, then he started to flail desperately as he called back to me.

“I’ll pay you, then,” shouted the Billionaire.

“What was that?” I shouted, rowing back in his direction.

“I’ll pay you,” he repeated.

“You’ll pay me?” I said, sitting up.

“How much do you want?” asked the Billionaire.

“How much do you have?” I asked.

“What?” said the Billionaire, bewildered.

“No wonder you’re sinking,” I said, “you’re weighed down by that watch and those rings. Give them to me so we’ll have more time to finish our negotiation.”

The Billionaire removed his watch and rings and threw them into my boat.

“I’m still sinking,” cried the Billionaire.

“Then give me your wallet,” I replied.

“Then can I get in the boat?”

“Certainly,” I said, “once you’ve paid my fee.”

“What is it?!”

”Everything.”

The Billionaire floated up for a moment, like a buoy, as if the shock of what I had said propelled him up.

“Everything?”

“Everything,” I repeated.

“You’re taking advantage of me,” said the Billionaire.

“It’s just the Market at work,” I said, “What is your life worth to you?”

The Billionaire held still for a long moment, the waves lapping at his chest.

“Could I… think about it?”

“As long as you like,” I said, holding up a life preserver, “but if you touch this, it means you have agreed to my price.”

The Billionaire backed away from the life preserver and looked off to the horizon.

“I mean… I’d still have my memories. My reputation.”

Glub.

“Or I could start over. That might be good. That might be… character-building.”

Glub.

“Or I could wait for someone else,” said the Billionaire as the preserver drifted away.

Glub.

“I mean, you’re not the only boat in the ocean—”

As I rowed back to shore, I could see him bobbing up and down as he considered his options. This continued for a minute or two and then all I could see was a ring of foam where he had been, as intermittent bubbles popped on the surface of the water.

Glub.